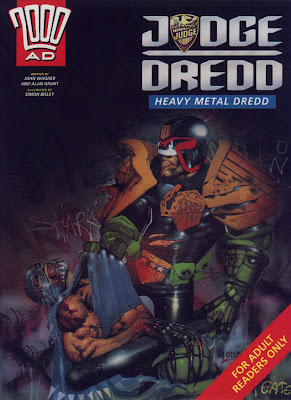

(Reprints Heavy Metal

Dredd stories from Judge Dredd

Megazine #1.14, 1.16-1.19, 2.13, 2.19, 2.21-2.25, 2.34-2.36, 2.61-2.62,

3.15, 3.17, 3.33)

The short-lived pan-European heavy metal magazine Rock Power launched in June, 1991; the

first issue's cover featured Skid Row, and also billed interior appearances by

the likes of LA Guns, Faith No More, Metallica and... Judge Dredd. For some

reason, they commissioned a series of six-page Dredd stories by John Wagner,

Alan Grant and Simon Bisley (at least at first), which mostly had something to

do with hard rock in one way or another, and were subsequently reprinted in

random issues of Judge Dredd Megazine whenever it needed some extra

content. Then, as I understand, there were more similar stories commissioned

for the Meg when the Rock Power ones ran out; they were

followed, then and in this collection, by early pieces that had initially

seemed not quite tasteful enough for Dredd's own title, or something.

(Speaking of the Megazine:

with this week's installment, we officially move into the period where David

Bishop was editing it. It's a fairly well-documented period, thanks to the

warts-and-all history that appeared in the Meg

itself, written by one David Bishop, who curiously refers to himself in the

third person throughout. As he does in Thrill-Power

Overload, for that matter. What I gather is that the creative budget for

the Megazine was trimmed around the time

he came on--it was rather extravagant for its time and place, hence the fancy

painted artwork in a lot of its strips--and Bishop started reprinting the Heavy Metal Dredd stuff as a cost-saving

measure.)

(There are also a handful of unreprinted-in-book-form

Dredd-universe strips from the final issues of the Megazine Vol. 1. John Wagner and Steve Sampson's "Brit-Cit

Babes" has one great selling point--a Brian Bolland cover on the first

issue in which it appeared--but it's distinctly lesser Wagner, and in fact he

apparently gave up on it midway through its final episode, leaving it to Bishop

to finish off. The Dave Stone-written, Brit-Cit-set "Armitage" has

continued to appear intermittently right up to the present. And Bishop and the

wonderful Roger Langridge collaborated on a comedy strip I've never seen, called

"The Straitjacket Fits"; given that they're both from New Zealand,

that has to be a reference to the Dunedin band of the same

name.)

But right: Heavy Metal

Dredd. That's heavy metal as in rock, but also Heavy Metal as in

Fluide Glacial-but-crasser:

visual spectacle trumps plot at every turn, what plot there is tends to be

pretty dumb, and the way-over-the-top hyperviolence seems to be more about

assuring their readers that this isn't namby-pamby kid stuff than anything else.

(It was apparently debated at length in the Megazine

letters section.) Eight of these stories are by the Wagner/Grant/Bisley team,

and none of them are as thrilling as any six-page cross-section of Judgment on Gotham. The polite John

Major-as-Batman type who gets his head bitten off in "Chicken Run" is

a nice touch, though.

Curiously, the Bisley episodes that work best are the ones

where he doesn't try to do a hastier version of his Judgment full-painting style: "The Great Arsoli" has a

spluttering Ralph Steadman-ish approach that's rarely been attempted in action

comics, and "Bimba" strips Bisley's technique down to very little

more than gestural doodles. (A lot of its its final page appears to have been

produced by Bisley deciding "fuck it" and seeing what he could do with

two Magic Markers in forty seconds. Don't try that at home.)

Commissioning editor Steve McManus asserted that HMD was out of continuity, "a

separate and aggressive Dredd world"; not much implies otherwise, and even

the version of Judge Karyn that appears in "Graceland" doesn't look

much like the familiar one. That might have something to do with the other

featured artist here, the late John Hicklenton, whose eight episodes might be the

closest Dredd has ever come to

"outsider art" (put that in as many sets of quotation marks as you

like). They're more Throbbing Gristle than L.A. Guns, really. Hicklenton, per

his interview in the Megazine in

2003, drew one episode while on acid in his tent at the Glastonbury music

festival; it says something that I can't tell which one.

Grant and Wagner weren't a particularly apt match for

Hicklenton--their scripts for him follow the "when all else fails, stupid

= funny" formula. Hicklenton was much more focused on grotesquerie than on stupidity, so John

Smith's scripts for a handful of these episodes were right up his alley. (I

believe these were the first published Dredd stories proper by Smith, a very

interesting if frequently frustrating writer whose early Devlin Waugh stories Graeme McMillan and I will be discussing at

some length here in a couple of weeks.) I mean, Dredd unzipping and emerging from a female-bodied fat suit? I can't think

of any earlier artist on the series who'd even have attempted to get away with that. Hicklenton didn't truck much with subtlety, though, as you can see below.

As for the three other artists who drew an episode apiece

during the Grant/Wagner period here: I do like Brendan McCarthy's work

on "The Ballad of Toad McFarlane," which gives him the opportunity to

draw psychedelic effects again, and even letterer Tom Frame gets to have a little fun in that episode,

returning to the eagle-shaped caption borders of "Oz." But how many Rock Power readers in 1992 would have

gotten the joke of the title?

Here's a question that's less rhetorical: I gather that Bisley's

very first Heavy Metal Dredd strip

was reprinted in a poster magazine included with 2000 AD #1068, but with entirely rewritten captions and dialogue.

Anybody able to confirm or deny that, and/or (if it's the case) explain how it happened?