(Reprints Judge Dredd stories from 2000 AD Progs 868-871, 928-937)

As Greil Marcus asked of Bob Dylan's Self Portrait: What is this shit?

By way of explanation, here's Mark Millar, interviewed in this month's Judge Dredd Megazine: "I only got into 2000 AD after I began working on it... I didn't realize how good 2000 AD was until much later on--and I hate to say this but I think I wrote some of the worst 2000 AD stories ever."

I'm not unreservedly down on Millar--I adore his Superman Adventures run, and his Ultimates and Authority have a crazy, barbed energy that's sometimes a lot of fun. But he's right: most of his 2000 AD material is just awful, stupid, condescending stuff, and his Dredd stories in particular totally miss what makes the series work when it works. Still, he's a big name now, in the post-Wanted/Kick-Ass world, and so is his former writing partner Grant Morrison, who had already published the excellent "Zenith" and "Dare" and Animal Man and Doom Patrol and the first few issues of The Invisibles by the time the Morrison/Millar-co-written "Crusade" appeared in 1995. That might explain the recent appearance of this slim, disastrously weak album with a handsome Brian Bolland cover (depicting the big-bad from "Crusade," who's set up for fifty pages or so before he's dispatched in a third-of-a-page fight with Dredd).

The ostensible premise of "Crusade" is that the Judges of Many Nations go to Antarctica to find a guy who claims he's seen God; they meet up, chat a bit, and decide to head off in separate directions, then spend the rest of the story trying to kill each other. As dumb as that is on its face, it's got other infelicities interrupting every few pages. Like the badass, crossbow-brandishing Vatican City judge, whose appearance suggests that everyone involved has forgotten about Devlin Waugh. Or the sinners bowing to a statue of "Ciccioliana" (sic) in the middle of the Vatican. Or the Indian judges being named "Sharma" and "Bhaji." Or the Pan-African judge being named "Daktari." Or the Japanese judge reprising the "ninja slices his enemy into pieces before he realizes what's happening" riff from Frank Miller's Daredevil in a grosser way, and then committing ritual suicide accompanied by a column of Japanese calligraphy. Or the dialogue's many lesser variations on "no, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die" (e.g. "Your priority should be staying alive, American!"). Or Dredd fulfilling a request to bring back someone who's discovered vital information by decapitating him and bringing back his head. And so on. All of this is made that much duller by Mick Austin's artwork, which is consistently ugly and garish--Austin gets a couple of stark, looming vistas across in the first few pages, but once the story degenerates into a gorefest, he starts phoning it in.

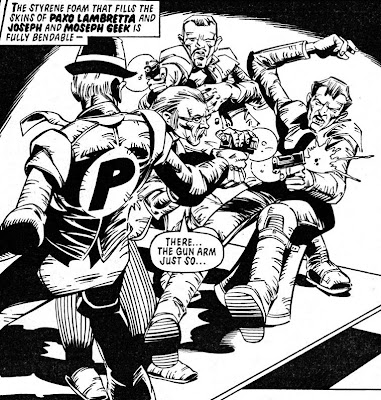

The short feature that follows the main attraction is the Millar-written "Frankenstein Division," which ran earlier--in the first four issues cover-dated 1994--and even manages to waste the talents of Carlos Ezquerra. Good on Millar for figuring that there would be repercussions from "The Apocalypse War" ten years later; too bad he appears not to have actually read it. So the Sovs have sewn together pieces of a bunch of their judges who Dredd personally killed in the war into a gigantic monster with a synthetic brain, which is supposed to be "the future of law enforcement." But where would they have gotten the corpses? Yeltsin and Andropov of East-Meg Two--and Millar must have tried really hard to make up those names--wouldn't have had access to the bodies of the Sov judges Dredd killed during the invasion of Mega-City One; they also wouldn't have had access to any of the bodies he left behind in East-Meg One, because the entire city was nuked.

A friend of mine recently pointed out a tic in bad Millar: his habit of repeating a word or phrase in dialogue. "Nothing will stop it. Nothing can stop it. There'll be hell to pay." "Nothing can stop me. And there'll be hell to pay... hell on earth!" "I beat you! I beat you good!" "My head--f-feel's [sic] like it's on fire! What's happening to my head?" "The place is on fire, drokk it!" Also, Millar quoting the Monks' "Nice Legs, Shame About the Face" in a scene about picking body parts to assemble into a monster constitutes justifiable grounds for throwing this book across the room.

Fortunately, it's pretty much all uphill from here in the Dreddverse bibliography: I can only think of a couple more volumes I'm not actively looking forward to reading or re-reading. Next week: Wilderlands, collecting the ambitious if ungainly crossover for which John Wagner returned to 2000 AD.