(Reprints Judge Dredd stories from 2000 AD Progs 970-999)

When it ended in mid-1996, The Pit was just shy of being the longest Judge Dredd storyline to date: 30 episodes to Necropolis-and-countdown's 31, heavily teased before its appearance (especially in the as-yet-unreprinted "Bad Frendz" sequence). It was a new approach for the series and for John Wagner, and a pretty terrific one; it was a down-to-earth antidote to the stumbles and overreaches of "Wilderlands." Even so, it doesn't quite seem to have the high reputation that earlier and later long storylines do. It has its admirers, but it's no Necropolis or Apocalypse War or The Day the Law Died or Total War or Tour of Duty, conventional wisdom has it.

Why is that? One possible explanation is that The Pit is the least visually appealing of all the Dredd epics. It starts out strongly, with Carlos Ezquerra in solid if not quite top form, but he drifts away fairly quickly, and only returns for three episodes in the middle and another three near the end. Colin MacNeil's episodes seem to have been turned around very quickly. Lee Sullivan had barely drawn Dredd before, Alex Ronald had only handled him in the G-rated Judge Dredd: Lawman of the Future series, and they really weren't ready for prime time yet. (See, for instance, Ronald's art on the second episode of "True Grot," in particular--it's almost nothing but shortcuts to avoid drawing anything tricky. He could do much better, and by the time of "Death Becomes Him" two years later he'd hit his stride, but in "The Pit" he's setting some kind of record for drawing characters' backs.)

"The Pit" also has a very different approach to what makes a "major Dredd story" from any other Wagner had written, although that's what I like so much about it. Once again, it's about the relationship between Dredd-as-the-law and the city, but this time it's focused on a particular detail of the city, and concerned with the general fallibility of person-as-law. There's not an individual bad apple to blame, like Cal or Kraken: nearly everyone in this story is corrupt to one degree or another, even Dredd. (When Warren complains that Dredd's got one law for DeMarco and another for him, he's basically right.) Everyone's acting fishy all the time, whether or not they're actually guilty. Dredd's the only one who believes that Lee's not lying about his gun having jammed--even DeMarco stands by Lee more out of solidarity than anything else.

DeMarco is Wagner's best invention in The Pit. She's a great character: a super-competent, stand-up cop who's convinced that her one vice is okay because it shouldn't be such a big deal. And she's right by the standards of everyone who's reading her story, and dead wrong by the standards of the subculture that's not just her subculture but the one she's chosen out of virtue when it would have been to her advantage to do otherwise. The Judge system's insistence on celibacy makes sex a bit like Bokononism in Kurt Vonnegut's Cat's Cradle: the thing that is utterly forbidden and that everyone does anyway. Think of the other Judges who've had liaisons of one kind or another: Fargo, Giant Senior... do people like Guthrie join the Wally Squad just so they can get laid without going to Titan?

The one image in The Pit that really rubs me the wrong way is the Mark Harrison cover, above, from Prog 987--not because it's cheesecake-y, but because that kind of cheesecake is off-register for the DeMarco we've seen, and because she seems to have gone up about five cup sizes all of a sudden. Compare it to Ezquerra's version of DeMarco in the early chapters, like the image below: she's buff like an athlete, not bombshell-curvy, and she's not conventionally pretty.

The first time we see DeMarco with Warren and understand what her "little secret" is, it's a shock to see her as a sexual entity--and it's a genuine accomplishment to defer that as long as Wagner and Ezquerra did, given that she's a young woman character in a fairly conventional adventure comic book. Anderson has had a "check out my butt!" vibe, to one extent or another, from the beginning; even Castillo, a year before The Pit, had an obligatory sequence early on in which she realizes that she might have a crush on Dredd. (To be fair, I don't think Hershey's ever been particularly sexualized, aside from that one "undercover" image of her in "The Candidates," and that's supposed to come off as creepy.)

As in Wilderlands, Wagner's juggling a whole lot of subplots and individual character arcs, but he manages to catch most of them this time. The big story is the "gruff old cop goes in to clean out a dirty precinct" plot, but we also have threads devoted to DeMarco, Lee, Buell, Warren, Guthrie, Argew, Priest, Patel and his father, and the suspicious circumstances around Rohan's death, as well as a few I'm probably forgetting. Most of them do get to resolve somehow--it's a fine Wagnerian touch that Rohan turns out to have died as an accidental side effect of judicial corruption, rather than to have been set up. The Fonzo Bongo business, though, seems grafted on at the end to provide a big action finale and let the characters who need to get killed get themselves killed. That's where Wagner really cuts corners: faced with the problem of explaining how Bongo's going to start a riot, he resolves it with a sign that says "RIOT TONITE 2000 HOURS SHARP - GREAT LOOTING OPPORTUNITIES." Funny, but a transparent bit of hand-waving.

Some of the characters who are supposed to be transformed thanks to Dredd's presence are simply declared to have changed: the story doesn't have quite enough room to set up the details of Buell's ascent, for instance. The joke is clear--Dredd, as the brilliant coach who comes in from the outside, is able to see great potential for loserly Buell in SJS because Buell's a friendless sadist--but we don't really get a sense of how Buell's found his calling, either. (That would come later.)

For all its ambition and all its entertainment value, though, the other reason that The Pit isn't quite up in the top rank of Dredd stories is that it's one of the few long serials that's had almost no lasting repercussions. 301 gets cleaned up, Bongo gets dealt with, and then Dredd goes back to his routine. It's mostly notable for the introduction of a few recurring characters, particularly DeMarco, in whom Wagner clearly saw further potential. We'll be seeing a lot of her over the next few months, including the "Doomsday" period when she takes over Castillo's "P.O.V. character for Megazine strips during a crossover while Dredd is otherwise occupied" role. Once Wagner wrote her out, she even got her own short-lived strip in the Megazine.

There's also one particular moment of The Pit I'd like to single out for praise, below. Could it be?

Yes indeed: it appears to be the sequence in which Judge Dredd, considered as a whole, after 19 years and 6000 or so pages, finally passes the Bechdel Test!

Yes indeed: it appears to be the sequence in which Judge Dredd, considered as a whole, after 19 years and 6000 or so pages, finally passes the Bechdel Test!

(Now, I could be a spoilsport and point out that the Bechdel Test, as it's usually interpreted, requires the women who talk to each other about something besides a man to be named characters, and that Judge Big Mohawked Blonde, even though she briefly appears in another episode too, never gets a name. But even so, The Pit squeaks through on the strength of a later sequence in which DeMarco and Castillo discuss how Castillo's doing after the fight and how DeMarco knows the jig is up since Castillo's appearance was a little too convenient, before the conversation turns back to the subject of Warren.)

(EDIT: I stand corrected! Lots of entirely reasonable earlier examples in this thread.)

(EDIT: I stand corrected! Lots of entirely reasonable earlier examples in this thread.)

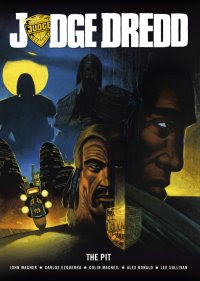

A trainspotting note: the Hamlyn edition, pictured up top, has the exact same contents as the current Rebellion version, but beats it hands down, just because it's bigger--and this was the period when, I believe, 2000 AD's page dimensions were as big as they've ever been. Hamlyn's version also has a cover (by the underused Jim Murray) that, as nondescript as it is, at least features Dredd prominently. The Colin MacNeil cover on the Rebellion edition, above--which originally ran on Prog 978, with the awful cover-line "Dark Justice!"--makes The Pit look like a Judge Giant-focused story, which it really isn't.

Next week: Mega-City Masters 01, an artist-focused collection of short Dredd stories that span several decades.

I would certainly rank The Pit as one of the great Dredd mega-stories, for pretty much all the reasons you give for its apparent lack of standing. Plot-wise, it doesn't have much in the way of lasting repercussions, but I think it does represent a definite shift in style and tone for the entire Dredd story.

ReplyDeleteUntil The Pit, almost every other character apart from Dredd was disposable to a certain degree, but this 30-parter helped establish a supporting cast for Dredd that were fascinating in their own right. DeMarco was such a success as a character because the reader actually cared what happened to her.

Whenever I try to tell people that Judge Dredd has been a truly great comic for the past decade, they usually ask me where that starts. And while I fumble around with that question (and often end up going all the way back to things like A Case For Treatment or even the Judge Child epilogue), I still believe The Pit is where the saga took on a tone of increased emotional complexity and real maturity that has guided it through the new millennium...

Another thing I really liked about The Pit was that you could tell Wagner had been influenced, directly or indirectly, by Ed McBain's 87th precinct novels, which were beautifully crafted pulp fiction about a big city detective building and the bulls who operated out of it and the multiple cases they were looking into at any one time.

DeletePretty much every 'realistic' cop show from Hill Street Blues onwards borrowed heavily from the novels, but this was the first time I'd seen that sort of storytelling done in comic book format and Wagner did it really, really well.

Tam: Wagner listed Hill Street Blues as his second favourite TV show in the profile which appeared in the 1989 Judge Dredd Annual. C4's US Football coverage ranked number 1, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest featured in book and film incarnations, his favourite car is the BMW 7 Series, and- in a shameless bit of self promotion- he picked The Outcasts as his favourite comic.

ReplyDeleteAnd of course, Hill Street Blues provided one of the worst puns in the strip's history, when Dredd and Anderson discovered that the Judges of 2120 had adopted a literal interpretation of the hitherto metaphorical accusation that they were feeding off the lifeblood of the population, in City of the Damned.

No, it's not one of the worst puns in the strip's history, it's THE worst pun. And considering there have been hundreds of terrible, terrible puns, (there are hundreds in the Daily Star strips alone, which were usually built around the pun-tastic punchline), that's saying a lot.

DeleteI dunno, I'd still give the crown to "J. Edgar Hover."

ReplyDelete'Bury My Knee At Wounded Heart' is more a case of disphasia or a particular form of spoonerism than a pun, but it certainly made me groan.

ReplyDeleteIIRC, I did contemplate changing the name of Bury My Knee - not because it was such a groan-inducing play on words, but because it was so tonally at odds with the story...

ReplyDeleteI love you, Bish-op.

DeleteI really liked the Pit as well, but I think one important thing was it really marked Dredd's evolution from a lone wolf into a leader. It put him up against problems that could not be solved by busting heads and managed to make his work as a manager and supervisor look as hard and as heroic as that of a street judge.

ReplyDeleteIt's a very 'mature' book in the sense of including grown up problems.