(Reprints: Judge

Dredd stories from 2000 AD Progs

776-803 and Judge Dredd Megazine

#2.01-2.11)

This week's guest is the remarkable Joe

"Jog" McCulloch, proprietor of Jog - The Blog, mastermind of

the Comics Journal's This

Week in Comics! column, and contributor to MUBI and the Los

Angeles Review of Books. Take it away, Joe!

JOE: If you'll allow it, I'd like to begin our

Sunday celebrations with a video clip. Unorthodox, I know, but I can't imagine

writing anything that could possibly convey the same raw enthusiasm for the

material at hand as exhibited by its writer, Mr. Garth Ennis himself:

A scrotnig

moment indeed to see the man behind Preacher

transformed into Chris Ware before your very eyes! And they didn't catch him on

a bad day or anything; probably the funniest recurring bit in David Bishop's Thrill-Power Overload is Ennis'

intermittent commentary on his own writing for 2000 AD, which is so completely and utterly negative (sample: "I

think if you examine it in detail you'll find it was, in fact, crap,")

that by the end you start coughing up a Pavlovian chuckle as soon as Ennis'

name appears. You wonder if maybe he isn't trying to wind Bishop up a little.

Yet there's an

uncomfortable aspect to all of this: he's basically right. Ennis scripts six of

the seven stories collected in this book, and none of them are very good. I'm

probably in the majority in saying that my favorite Ennis Dredd pieces -- and I

haven't read all of them, mind you -- are the conversational or declaratory

character things, like the Muzak Killer stories where it's nothing but 21,

22-year old Garth Ennis railing about music while Dermot Power lays down

photorealist images of Sinéad O'Connor being shot in the head. There you get

some sense of an angry young man's unrefined energy, which is often something

that gets smothered under the expectations of work-for-hire production on a

superhero property you haven't created.

And yes, for

the purposes of this Feast of Ennis, I'm counting Judge Dredd as a

work-for-hire superhero property, because structurally -- insofar as Ennis is

tasked with following a 'core' characterization established by a prior, popular

writer (actually the co-creator, fine Pennsylvania native John Wagner, in this

case), with the weight of longstanding fan expectations and content

restrictions hanging over him -- that's exactly what it is. The irony, then, is

obvious: because Ennis is unique among writers of North American comic

book-type comics in avoiding work-for-hire superhero production as much as

possible -- and, when so moved, infusing preexisting superhero properties with

an extremely distinct point of view, well beyond the unique writerly voices of

your Grant Morrisons or Mark Millars, since those writers can blend their

perspectives into the overriding idea of the ongoing superhero 'universe,'

while Ennis, with only Warren Ellis even approaching him on that front, can

only ever write Garth Ennis Comics -- the prospect of seeing him absorbed fully

into such an environment so early in his career can only make the stuff

intriguing to devout readers, no matter how weak the comics themselves are.

I concede, of

course, that there's other elements at play, and that there's a keen difference

between structural and substantive work-for-hire superhero comics. Morrison and

Millar have unmistakable writerly voices, but they also claim a great personal

affection for U.S. superhero comics and their particular traits. Ennis has no

such thing, so he might simply be less willing to sink himself into the

substance of capes 'n tights American superheroes, even when the evident

financial benefits of working on such comics inspire his participation. In

contrast, Ennis is on the record many times as having a great, nostalgic

affection for Dredd and 2000 AD,

rough and violent and nasty-thrilling childhood favorites, so it could be that

a writer who started out, we must remember, writing what now would be termed 'literary

comics' via Troubled Souls at Crisis, became willingly swallowed by

the substance of Dredd without having the experience to maintain interesting or

effective storytelling.

An example from

Case Files 17 will probably help. The

absolute worst thing in the book is "A Magic Place," illustrated in

different chapters by Steve Dillon and Simon Coleby, both working in collaboration

with the mysterious "Hart," whom I will presume is colorist Gina

Hart, sadly uncredited anywhere else in the book (which, furthermore, due to

the formatting of the included issues of Judge

Dredd Megazine, neglects to specify which artists exactly worked on those

stories, and actually omits the title of one of those stories altogether; not a

bug-free project yet, I'm afraid). It is a quintessential Bad Superhero Comic,

and not just because of the fill-in art. No, this is a creature of continuity,

a direct follow-up to "Beyond the Wall," one of Dillon's stories from

the 2000 AD Sci-Fi Special 1986

(written by Wagner & Alan Grant, reprinted in The Restricted Files 2), seeing a pair of star-crossed lover

characters frolicking in a peaceable agrarian setting five years later. Then an

evil supervillain in a chef's costume invades their space wielding a deadly

blender and subjects them to PG-13-rated terror until the boy half of the

equation gets himself shot while warning the Judges about the threat, after

which Dredd kills the bad people and the boy dies clutching a rose -- HIS LOVER

IS NAMED "ROSIE" YOU SEE -- having cleared villainous landmines from

the beloved garden that symbolizes the promise of life and peace and love and

etc.

The problem is,

the extraordinary sentimentality of this scenario is totally devoid of actual

emotional effect unless you've read the original story; like an American

superhero writer leaning hard on our memories of past adventures in scratching

the outline of an emotional arc and calling it a proper story, Ennis has his

doomed protagonist narrate his emotional history with this woman via captions

and flatly state the metaphor behind concrete blocks vs. organic settings in

expository dialogue -- your review of the Restricted Files 2 suggests that a

b&w vs. color effect is used in the original, which sounds better -- before

everything goes to hell in a purportedly scalding a heartbreaking manner. Which

leads us to problem #2: the man taking everything to hell is a dude in chef's

hat swinging a deadly blender, which would have seemed Dredd-apropos yet

entirely ridiculous in a would-be shattering human story even if Ennis wasn't

further held back by content restrictions leaving the home invasion element

seeming like a 10:00 PM network television edit of Fight for Your Life. Although query, I guess, whether this is

nominally better or worse than a guy with a fin on his head raping women in Justice League crossovers.

What makes

this story bad isn't just Ennis' inexperience, then, but his inability to parse

his affection for Dredd tropes -- and the necessity for him to deal with those

tropes in terms of fan/editorial expectations -- so that they don't sabotage

the story he's trying to tell. A few weeks ago you stated that "Wagner's version of Dredd is a

useful monster; Ennis's is tough enough to do hard things," suggesting

that the young Ennis' love for the character blinded him, in a fannish way,

from the deeper implications of the concept. I both agree and disagree, insofar

as I think Ennis does absolutely understand that Dredd is a monster -- far and

away the best part of "A Magic Place" is two panels segueing from the

evil chef walloping the boy to Dredd crunching a young perp's balls, though

Ennis then gilds the lily by pointing out his own cleverness via caption -- but

he's also hesitant to actually explore the character in a way that might upset

Wagner's baseline, which we might even qualify as a matter of respecting

creator's rights, should we agree that characters ought really never be written

by anyone other than the creators, although that kind of approach is obviously

anathematic to American superhero comics along with most of 2000 AD's history, and indeed would have

squelched the whole British Invasion thing from the start, to say nothing of

the Hellblazer comics Ennis was

already writing at this time, where he truly began to cast off the burden of

fidelity and make Garth Ennis Comics.

DOUGLAS:

I'd agree that Ennis was having a very hard time channeling his fondness for

the Wagner incarnation into stories that felt like Garth Ennis Comics;

sometimes his Dredd crossed the line into something close to John Wagner fan-fiction,

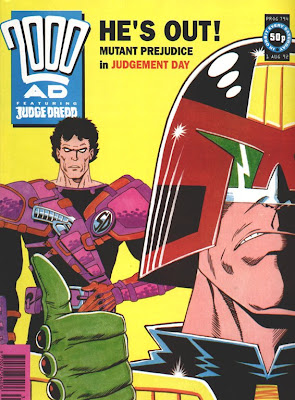

and never more than the end of "Judgement Day," with the two big

Wagner/Carlos Ezquerra characters--now, at least for a while, Ennis/Ezquerra

characters--stomping off into the dust, growling "who the hell's gonna

mess with us?" Dredd and Stront

sure are awesome, all right! (It's weird how hard it is to get out from Wagner's

shadow on Dredd. I'll be getting around to Grant Morrison and Ezquerra's "Inferno"

when Case Files 19 comes out a bit

later this year, but I recently read it for the first time, and was alarmed to

see Morrison, of all writers, losing his "unmistakable writerly voice"

almost completely in trying to play back old Wagner beats louder.) Eight years

after his main run ended, Ennis returned to Dredd for "Helter Skelter,"

which is probably stronger for acknowledging outright that it's 2000 AD fanfic. (He talks in this brief interview about "the memory of reading it weekly as a kid and somehow always feeling just a little bit happier afterwards.")

I don't love "A Magic Place" either, but

my suspicion--unconfirmed by anything I've read, just circumstantial

evidence--is that it was a last-second fill-in to mark time before "Judgement

Day" began. After twenty monthly issues, Judge Dredd: The Megazine was relaunched in May 1992 as a biweekly,

with a lower page count (44) and a lower cover price (99p). Wagner hadn't

published a Dredd story proper in six months or so at that point, but returned

to write the flagship feature in the first issue--"Texas City Sting,"

a fluffy little collaboration with an artist who'd never drawn Dredd before, Yan

Shimony (with Gina Hart again coloring).

That makes no sense for a big relaunch, and when

an artist as fast as Steve Dillon only draws the first part of a three-part

story, I have to suspect that there's a real time-crunch issue. It seems

possible, anyway, that "Judgement Day" was meant to start six weeks

earlier, to be part of the first issue of the relaunched Megazine, but that when it hit schedule problems it was bumped

back, with the evergreen "Almighty Dredd" and the hastily whisked

together "Texas City Sting" and "A Magic Place" vamping

until it was ready. (It may also have been pointed out that Dredd himself

barely even appears in the first Megazine

chapter of "Judgement Day.")

In any case, the second Megazine issue's text pages include a couple of surprises. They

explain the shape of "Judgement Day," and note that Dean Ormston will

be painting most of the Megazine

episodes but that "rising new star" Chris Halls will paint one--Jog,

I think you get to tell a bit more about Halls! And they include what I suspect

is the first appearance of Judge Pal, a bit of business that's more recently

become a favorite subplot of current Dredd-writer-when-Wagner's-not-around Al

Ewing, who also recently took over from Ennis on his co-creation Jennifer

Blood. (Anyone know if Pal turned up anywhere before this?)

JOE: Ha, I actually do have an earlier Judge Pal

appearance! For a little while, Fleetway was putting out these 48-page

'Prestige Format' editions of the Megazine

for the U.S. market; issue #2 arrived at some undisclosed moment in mid-to-late

1991 (so, close to a year after the U.K. edition), and what did we get on the

inside front cover?

DOUGLAS: Jesus. You really have read

every comic ever.

But yes, "Judgement Day" occupies a

solid half of this volume, and I think it exemplifies what didn't work about

the Ennis era. It's a relatively huge story, the first of the three big

crossovers between 2000 AD and the Megazine--20 chapters, drawn by four

artists. The first page credits Wagner for co-plotting it with Ennis, who's

said that Wagner's contribution really only consisted of suggesting that

another big epic would be a good idea and that zombies seemed to be pretty hot

at the time.

It's thoughtful of Ennis to take the blame for it,

anyway. As he's noted, it's basically his attempt to rewrite "The

Apocalypse War," and he recycles bits of that era's Dredd stories all over

it: the bang-and-they're-gone deaths of Dekker and Perrier are Giant's death,

the singing-and-dancing zombies recapitulate the guy singing while the bombs

fall on the southern sectors, the fight at the wall is the Dan Tanna Junction

sequence--when somebody tells Dredd that "the gun barrels are overheating,"

I'm amazed Ennis doesn't follow it with the exploding-guns routine again.

Sabbat is essentially Judge Death with much worse character design (and no

motivation for wanting to kill everyone other than that he's very bad, and comedy-relief

trappings from his first appearance). And, of course, Ennis tries to top the "nuking

East-Meg One" sequence from "The Apocalypse War" with the one

where Dredd orders five cities nuked.

So I'd agree that this is a bad superhero comic,

and I think one crucial aspect of its badness was slightly ahead of its time: "remember

that thing you loved? Here it is again!" This is one of the few times that

"Judge Dredd" has directly appealed to its readers' memories of what the series used to be like, as opposed

to returning to some previously established plot point or character (as in "A

Magic Place"). You start doing that shit and you end up with a "classic

era," and before you know it you're Teen

Titans, sitting on a street corner with a facial tattoo of the splash page

of "Who Is Donna Troy?"

In particular, the kill-'em-all moment in

"Judgement Day" doesn't have anything like the same impact as its

model, partly because Wagner pulled that trick already, and mostly because it's

presented as not being particularly monstrous. Destroying East-Meg One was an

atrocity of war, and a potentially unjustified act of rage--a moment where as

readers we're set up to cheer and also be horrified that we're cheering. What

Ennis's Dredd does here, though, is presented as unfortunate but necessary, and

anyway almost everyone in those cities is dead already so it's not that big a

deal, right?, and it's a good thing there was somebody tough enough to make

that hard call. It's also had very little in the way of long-term consequences,

while Dredd's hand in the genocide of East-Meg One has reverberated for

decades.

That's another strength of Wagner's (and Grant's)

that Ennis lacked at this point: long-term planning. "The Apocalypse

War" and "Necropolis," and to some extent "Oz," had

gradual ramp-ups to their beginnings, and shifted the course of the series

after they ended. "Judgement Day" all but begins "one day, Judge

Dredd and some cadets were out on a hotdog run..." And once it ends--our

hero decapitates the bad guy and sticks his head on a plot device, and the

global threat abruptly stops--that's all but it: how about those zombies, huh?

(There are a few references to "Judgement Day" in subsequent stories,

but Ennis's only real attempt to deal with it as having long-term consequences

was a six-page epilogue, "The Kinda Dead Man," that appeared a few

months later and serves as a postscript in the DC edition of Judgement Day.) All of those long

stories also offer some kind of angle on the relationship between the

man-as-law and the city; this one's about Dredd and a bunch of international

judges fighting zombies.

But you touch on one of the hallmarks of Ennis's

comics: how much he likes to use familiar superhero types as spittoons, all the

way up to The Boys. "The

Marshal" is the resident superheroes-suck story here, and it's a very

strange one, despite some nice painted art by Sean Phillips in his "my

brushstrokes, let me show you them" mode. The murderous antagonist who

goes around bellowing about wanting justice has a cape and mask and climbs up

walls and so forth--he even keeps his mask on when he's being interrogated,

which is a good trick--and he turns out to be part of a mutant cargo cult

inspired by Tonto, as in that other engine of Dynamite Entertainment, the Lone Ranger.

There's that name, though: why call him "The

Marshal"? Might that have something to do with (heavily 2000 AD-associated) Pat Mills and Kevin

O'Neill's own superhero-kicking vehicle Marshal

Law, which had debuted a few years earlier? I have no idea--although I

think you've mentioned something about the impact Mills seems to have had on

Ennis's writing. Tell me more!

And to get back to the "Dredd the

monster" thing one more time: I wouldn't say that Ennis was blind to the

darker implications of the character, but I do think he wrote Dredd as being ultimately admirable with very little

equivocation. A lot of Ennis's favorite protagonists have been, one way or

another, straight-shooting tough guys who kill them that need killin' and die

with their boots on &c.: Jesse Custer, Tommy Monaghan, Frank Castle, and on

and on. (Part of why I like his Hellblazer

so much is that his John Constantine is more complicated than that.) His Dredd,

I think, is part of that line--excessively violent sometimes, maybe, but still

someone to whom law-abiding citizens ought to give thanks for being made of

sterner stuff than themselves. Who the hell's gonna mess with him?

JOE: Hmm, I think you’re simplifying Ennis’

attitudes toward his own characters. Or, rather, how his characters function in

his narrative schemes. Take Frank Castle, whom I feel is closest to Dredd in

general disposition, and almost acts as a successor in terms of Ennis’ body of

work - 1995’s The Punisher Kills the

Marvel Universe was Ennis’ first comic for Marvel, and it showed up just a

few months after the aptly titled "Goodnight Kiss," Ennis’ final

Dredd (and 2000 AD) contribution for

the 20th century.

Unlike with the

good Judge, however, Ennis did not appear to have any particular history with

the character, and certainly no relationship with his creators; honestly, it’s

probably a tiny klatch of dorks indeed that can name Gerry Conway (ORIGINATING

WRITER!) John Romita, Sr. (VISUAL DESIGN!) and Ross Andru (INITIAL ARTIST!) as

creators of the Punisher, going way back in his mid-’70s villain days in The Amazing Spider-Man. Castle has been

something of a malleable character since then, which probably made him an ideal

means of conveying Ennis’ mockery of American superhero substance and general

yen for funny violence, since what few continuing traits he had -- a desire for

vengeance on crime, an outsider stance toward the superhero orthodoxy, an

extensive armory -- were adaptable to Ennis’ aims, which continued through two

millennial series under the Marvel Knights imprint. Amazingly, the gap between

the two series was graced by Ennis’ return to Dredd with "Helter Skelter,"

though I’m sure the actual writing of these series couldn’t have occurred in

quite so neat a manner, nor could Ennis have possibly planned that his very

last Dredd story thus far, 2003’s "Monkey on My Back," would have

concluded the very same month that an all-new, all-different Punisher launched.

That was "Born," the first Punisher MAX series, an expanded pre-origin war story set in Vietnam;

it wasn’t clear at first, but Ennis was building a new and discreet universe

for his ‘serious’ Castle, one with no superheroes and a well-defined beginning,

middle and end. The proper Punisher MAX series launched in 2004, adopting a

very Dredd-like quasi-realtime scheme, so that the characters could age along

with their readership. This proved to be thematically apt, as it eventually

became clear that Ennis was telling a long, damning, nihilistic life’s saga, by

which Castle’s actions, though nominally satisfying in that he’s killing some

really bad people, are eventually shown to provoke future horrible acts. In

other words, he ‘wins’ from story to story, but putting the stories together

undercuts his accomplishments, sabotaging the arguable heroism of his actions. This

concept has a political dimension -- the first quasi-realtime MAX story (2004)

has government agents trying to recruit Castle for the War on Terror, while the

last one (2008) prominently links the character’s Vietnam origins to the Iraq

War, which the attentive reader gravely notes has been going on for the series’

entire run, both in and out of the comic -- but it eventually becomes integral

to Ennis’ development of the Frank Castle, who eventually admits to himself

that he could break the cycle and begin his life over again, but he can’t, he

just can’t.

In this way,

Ennis doesn’t so much equivocate as to whether Castle is a monster, but wires

that truth into the very fabric of his world, a freedom of insight he could

never have with Dredd. Yet the similarities between the characters become

especially evident in 2004’s The End one-shot, which was far from the last

Punisher comic Ennis wrote but served as terminus for his private MAX universe.

There, following a nuclear exchange at an undisclosed point in the future,

Castle eliminates the last living humans for their crimes before staggering out

into an irradiated wasteland - taking the Long Walk into the Cursed Earth. But

here the entire globe is cursed, and Castle is totally alone, because he’s

brought the Law to everyone that didn’t live up, which is to say everyone. The

series then launches itself into a dizzying meta level as Castle narrates a

vision he has of his family having their picnic in the park, hoping he’ll be

able to save them and avert his own origin. Of course, we know he’ll fail. He’s

a corporate-owned superhero character, in structure if not substance. He will

watch his family die over and over and over and over, and his life will be

ruined, ruined, ruined, because that’s what gives him value.

To live in a

superhero universe is to live in eternal, lucrative conflict. It is to live in

Hell.

It’s Ennis’

most eloquent dissent to the superhero scheme, and I feel particularly

charged-up to be recounting it on this National Before Watchmen Week.

This is why, to

my mind, Ennis’ Punisher embodies both poles of the Garth Ennis Comic - the

funny and the serious. Because when Ennis’ comics are ‘serious,’ they’re still

gruesome and violent, but they’re fundamentally about the tension between the

appeal of hard man violence -- and, on another level, the pleasure derived from

reading it -- and the understanding that such things typically act in the

service of systemic peril. This is the subtext of many of his war comics, which

sometimes pair an uncertain or passive or restrained with a harsher, less

humane counterpart in a sort of dialectic; the system of War is conductive to

inhumanity, and the struggle, then, is about resisting the system, even through

the awareness that it’s arguably in place to accomplish some greater good. And

it’s a genre system too - it’s hard for me to look at a commando comic-derived

2000 AD serial like "Invasion!" without seeing a mad Ennis anti-hero in the role

of its shotgun-wielding wild man freedom fighter. You can imagine my delight to

later discover that one of Ennis’ rejected pitches involved just that

character, recast as an unrehabilitated lunatic in a post-war world.

DOUGLAS: OK--I'm convinced by your argument! Also, I've

now gone from thinking I should maybe get around to reading more than bits and

pieces of Ennis' Punisher one of

these days to realizing that I need to. Just a few side notes on this:

There was one

other significant contributor to the Punisher's initial development, and I only

mention this because it's a great story. From Tom Spurgeon and Jordan Raphael's

Stan Lee and the Rise and Fall of the

American Comic Book:

Castle's

costume, a tight-fitting black suit with a large white skull on the chest,

looked fearsome enough, but the character lacked a suitable nom de guerre.

Conway and [Len] Wein, who was then editor in chief, sought Stan's counsel.

"What does

this guy do?" Stan asked.

"He's an

ex-army guy whose family was killed by the Mob. He goes out and punishes the

underworld," Wein responded.

Lee thought for

a moment. "He's the Punisher."

Wein says that

you could hear the sound of the two men slapping their foreheads--"Of course!"--at

the flawless simplicity of the name.

(Maybe that

makes Pat Mills, who came up with the name "Judge Dread" (sic) for a

series that initially looked very different, the Stan Lee figure here? I'm just

starting to get into Mills' later iteration of "Savage," in which "Invasion!"'s

shotgun-wielding wild man freedom fighter Bill Savage doesn't have quite so

much of the moral high ground above the Volgans...)

It's kind of

funny that we know now that Dredd was Wagner and Ezquerra's creation, but that

would have been even more unclear than the Punisher's background to readers in

the early years of the series. Ezquerra only drew three complete episodes

before "The Apocalypse War," almost five years in: "Bank

Raid" (the first completed story, written by Wagner and Mills, and shelved

until the 1981 Judge Dredd Annual),

"Krong," written by Malcolm Shaw, in 2000 AD #5, and the first installment of Wagner's "Robot

Wars" in #10--all, I believe, uncredited at the time.

I've only seen

the first episode of Ennis and Curse of

the Crimson Corsair artist John Higgins' three-part "Monkey

on My Back," but curiously enough it's effectively "Judge Dredd: The

Beginning"--it's set in January 2099, not long before Dredd's first

appearance in 2000 AD, and involves a

judge who's wandered into the city from the Cursed Earth.

But I

interrupted you, sorry--

JOE: "Savage" is a lot of fun; I like Patrick Goddard’s art a ton,

though I could have done without the robot stuff in the most recent one. But

then, a writer maintaining his own personal continuity can lead to trouble too.

You mentioned Mills

before - I do see a bit of him in Ennis, mainly in how Ennis enjoys pitting

damaged goods against establishment forces, and how odd moments of broad humor

burst in on the drama at unexpected moments. Marshal Law indeed seems extremely simpatico with Ennis’ take on

American superhero culture, though it’s honestly a more radical work than many

of Ennis’ series; maybe not The Punisher

MAX, but certainly The Boys,

which despite its wee slaps aimed at the stretch-pants set -- to say nothing of

the nominal and tragic-familial similarities between Bill Savage and Billy Butcher

-- is secretly one of the most old-school, Bronze Age-y superhero series on the

stands today with its looooong simmering plotlines and heavy, soap operatic

relationship drama. It’s also a hopeful work, insofar as Ennis seems intent on

leaving open the possibility for real heroism to exist in the world; Marshal Law initially reserved that

benediction for the dead, as part of its wider metaphor of superhumans as

soldiers - beneficiaries of a world Superpower. Very post-Watchmen, at least

until it went to hell all weighed down with excessive spoofing, which frankly

isn’t Ennis’ strong point either. I suspect the very fact that he sincerely doesn’t care about superheroes all that

much has denied him the background necessary to really take the piss out of the

scene effectively; all of his parodies read like a guy who knows some

Silver/Marvel Age and maybe glanced at some ‘90s stuff long enough to get a

bellyache.

This brings us back

to "The Marshal," which is definitely my favorite piece in Case Files 17. Part of that’s because

Sean Phillips’ painting is consistent and pretty clean in conveying the

action-heavy nature of the script -- in contrast, I couldn’t even tell what was

going on at times with Greg Staples’ arguably more stylish, Hewlettesque paints

on "Babes in Arms," a soppy would-be action-story-with-a-heart

notable mainly for a magnificently dubious "Dredd is actually a

monster" moment wherein one of the story’s battered, vengeance-seeking

ex-wives peers around the corner and Our Man wallops her right in face, just

like her husband -- but it’s also due to Ennis dipping into his fascination

with Americana. He’s mentioned in interviews the powerful formative effect

westerns and cowboy iconography had on him as a child, so it feels somehow

necessary that this particular stream of interest -- at its most prominent in Preacher -- should splash into Dredd and

2000 AD. It’s also the only one of

Ennis’ stories in here that clicks with the classic Dredd subtext: a view of

America as seen by foreigners. And while Ennis surely loves America as much as

he loves Dredd, he’s more vigorous (if not much more skillful at this point) in

lodging criticism; it’s a Cowboys and Indians yarn, with the mutant Marshal

basing his life on Tonto, seeking metaphoric vengeance for the atrocities

committed on native peoples by younger Americans. The white baddie is put away,

but the outcast dies, and the Law doesn’t really give a shit. Blunt, but at

least from here you can see where Ennis is going.

(The obverse effect

can be seen in another Ennis Britcomics revival: his 2007-08 Dan Dare series with Gary Erskine, an

old-timey space opera that amounts to the most romantic, heroic, black and

white chocks away war story Ennis has ever written, yet done by that point with

enough of his career in focus so we can see an implicit criticism: that such

gallantry can only really exist in a sci-fi setting intended for children,

conveyed in a duly childlike manner.)

Of course, you can

also see where some things are going with Judgement Day; I totally, totally

agree with you that it’s a little ahead of its time in fan-flattering Greatest

Hits citation, and I’ll even go further in invoking both Tim O’Neil’s concept

of superhero momentism -- a style of writing centered around the

chase for iconic 'moments' in which the cumulative cool factor of a superhero

character is distilled into a whoop-ass pump-your-fists image or sequence that

gets the fans to their feet -- and, moreover, the unctuous faux-momentism of

supporting characters standing around and simply telling us how impossibly

fucking great the lead character inarguably is. "Judgement Day" is

lousy with all of that, even on top of the primal superhero crossover impetus:

goosing short-term sales, here with an eye toward the fortnightly returns of Judge Dredd Megazine, per David Bishop.

Still, "Judgement

Day" isn’t quite the superhero crossover at its worst, since one writer is

in charge of everything (aside from Wagner’s initial storyline tip-off), and no

other ongoing stories are interrupted. And while I agree with all of your

criticisms of the story -- Abhay Khosla once suggested that dead boring antagonists are endemic to

superhero crossovers, and by that standard Sabbat’s one for the record books --

I find the whole thing oddly sympathetic as an attempt to toss out the

ponderousness of world-shattering Event mechanics (if such notions had even

entered Ennis' mind) and just do a 150-page barrage of action scenes. But then

you get into another recurring problem with both superhero crossovers and the

stories in Case Files 17 - the art

quality varies a lot, and that's just toxic when you're trying to build mad

chains of activity on the page. So for five chapters you get Peter Doherty, who

acquits himself fairly well with a shimmery, misty painted approach that whips

up some decent creepy zombies and ugly gore, and then for five chapters (not

consecutively, mind you) you get the intermittently striking, mostly dreary

heavy shadows of Dean Ormston, who does the heavy-paints-interspersed-with-quick-sketches

Bisley thing to awkward effect, particularly when it looks like he's got

deadline doom snapping at his heels (Part 18 is a disaster). Granted, this was

early work for him. Same for Doherty. Hell, same for Staples earlier in the

book.

Definitely the same

for Chris Halls, who had debuted as a cover artist for the Megazine the month prior to his one and only chapter, and was

subsequently never seen on first-run interior comics pages again; he did,

however, provide the Mean Machine makeup effects on the beloved 1995 Judge Dredd motion picture, which

apparently caught the eye of Stanley Kubrick (whom I imagine threw his fruit

punch at the screen as soon as Stallone removed the helmet) and launched Halls

to ever-higher prominence in the cinematographic arts under his birth name of

Chris Cunningham. Yes, Come to Daddy Chris Cunningham. All is Full of Love Chris Cunningham. Frozen Chris Cunningham - I know I'll be thinking of

Judge Dredd more than usual at halftime today. But while this is all very

amusing, much like the time Paul Thomas Anderson drew comics under the name

"Stephen Platt" (NOTE: this is a lie), Cunningham's art is actually

rather fascinating in being SO green that its blend of blatant Bisley licks,

monochrome drawings, shadowplay and near-abstract, potentially computerized

images of nuclear annihilation is like witnessing an artist putting things

together in his head, somehow in front of you.

Still, the star of

both "Judgement Day" and Case

Files 17 as a whole can only be Carlos Ezquerra, rocking his very much not

green cartoon style in brazen defiance of the painterly strokes of everyone

else (though I think he actually is painting the colors). Squat in faces and

curvy in architecture, there's something about Ezquerra's look in this period

that's almost manga-like, specifically a Masamune Shirow-type Euro-informed

approach, willing to set stylized figures in a detailed, heavy, but distinctly

drawn setting, something that blends right in with the racing lines of many,

many scenes of violent activity. His art in another story, "Taking of

Sector 123," is even better:

I love it! "Sector

123" is another nothing story, a Dredd putting down a revolution

story/goths are weaklings story, but a really good artist can coax out the

fundamental emphasis on action and thereby make it seems a bit more fittingly

Dredd, and therefore a little more worthwhile. That's the backing of Dredd, the

default Thrill, but a lot of the artists in here don't have what it takes to

push it. You can't just write this stuff.

DOUGLAS: That Ezquerra page is just great, but then most of them are. This is

probably my favorite era of his art, when he got to do that supersaturated color work but

hadn't yet switched over to the too-airbrushed computer coloring of his recent

stuff. Everything about that page's composition just works. The inset images of the freaking-out 123'ers and the

cucumber-cool gunner are the same size and shape but at opposite corners of the

page; Dredd's cycle is aimed at the revolutionaries and butting into their

panel; the curve of the cycle lights' position and the bike's movement are

balanced with the Gunbird's curve and its stasis; the ship is pointed right at

the image of the gunner, as a hint that we're seeing what's happening inside

it; the few details of the buildings we can see imply a lot that we don't;

every image on the page has a different enough color scheme that the eye bounds

right from one to the next... that kind of balance of total clarity and brute

force is rare and wonderful.

Ezquerra's

also much better than anyone else in this volume at the very basic act of

indicating what's going on in any given scene, where it's happening, etc.

Doherty gives us a little glimpse of Sabbat's cloak-made-out-of-souls in the

first chapter of "Judgement Day," and Ormston knows it's there, but as soon as Ezquerra arrives

he makes sure we get a good look. I do like the "Chris Halls" chapter

a lot, though, Bisley-isms and all--that panel you pulled out for your TCJ column a few weeks ago is terrific. (An especially

nice detail: Dredd's helmet and outfit are the only areas of solid black in the

image, and the zigzag reflection in his visor is the only pure-white detail

without spraypaint speckles.)

As for

additional Halls interior art: This site claims that

there was a story called "Aliens: Matrix" by Halls and Grant Morrison (!!) that was supposed to appear in the British Aliens Magazine #23, two issues after the final one that actually

got printed. If that actually exists somewhere, I think I would not be the only

one who would be very curious to see it...

It's interesting

to think of "Judgement Day" as a superhero crossover, although I

suppose it is just in terms of having to cater to the regular readers of two

ongoing publications who probably overlap but might not (while, ideally,

attracting readers to the lower-circulation series and convincing them to stick

around). It was the first of three major crossovers between 2000 AD and the Megazine. The second was 1994's "Wilderlands"; Wagner

wrote that one with an eye to making sure readers of one series but not the

other wouldn't miss anything important happening, with the result that not very

much of import happens at all. 1999's "Doomsday Scenario," also

written by Wagner, was better planned (following two separate, simultaneous

sets of events), but they haven't really tried attempted a big crossover since.

("Judgement Day" is maybe more a crossover in the sense that it's got

Johnny Alpha in it, although for the life of me I've never figured out what

he's doing in the story. Or why Brett Ewins drew one of its covers.)

As for

"momentism": yeah, that's true enough of "Judgement Day,"

but I think it's interesting that a lot of the really memorable character moments

of Dredd as a series overall--the ones that get callbacks later on--are either

things that happen in passing (Dredd interrogating De Gaulle, DeMarco kissing

him) or things that happen to other characters (the revelation of Rico's face, Chopper

being led away while everyone shouts his name). For all the times Dredd's had "I AM THE LAW!" stuck in a word balloon, I don't think there's ever been

a particularly notable bring-up-the-Hans-Zimmer-music one, and thank heaven for that. "Gaze into the fist

of Dredd!" is as close as it gets, and nobody's going back to that well.

True enough

that Dredd's always been a view of America from abroad--although you could say

as much for a lot of post-British Invasion American mainstream comics writing,

from Watchmen on down through

Morrison and Ellis and Gaiman and so on. (I'm trying to imagine how an American

writing something along the lines of "Whatever happened to the British

dream? You're looking at it" would come off.) One of the things that makes

Dredd particularly interesting to me, though, is that it's a view of America

from the British Isles and for a

British audience. Which is why the American cultural references in Dredd always surprise me a little, e.g.

Ennis calling his Referendum story "Twilight's Last Gleaming,"

roughly the equivalent of calling a story to be published in the U.S.

"Frustrate Their Knavish Tricks." Cf. Alan Moore joking that "we

had to put up with those references to Benedict Arnold in Superboy without knowing who he was." That's also another

point of difference with regard to Ennis's Dan

Dare: Dare is, more than any other comics character of his kind and

caliber, British to the core. Of course, Ennis is Northern Irish, which puts

yet another spin on it. But you're better equipped to talk about where Dredd

sits within Ennis's body of work than I am...

JOE: “Nobody's going back to

that well.” A rare sentiment these days, Douglas. It reminds me of "Helter

Skelter," which we’ve mentioned a few times; Ennis did that story as a

mature writer, as a means of dealing with his past, but not just on the page;

part of the deal was that he (and I presume artist John McCrea) would get

the rights to his (their) very first comic, the literary comic, "Troubled

Souls," if Ennis agreed to return to Mega-City One. I suspect he may have

done it to ensure the legalities remained in order for his and McCrea’s comedy

series Dicks -- since the lead

characters there had first appeared in "Troubled Souls" -- and,

possibly, also to give his debutante work a proper burial, a la Chris Ware and Floyd Farland: Citizen of the Future. BOOM!

BOOKEND!

That’s the funny thing

about 2000 AD and its sibling magazines - sometimes people do get their stuff

back. I know Rian Hughes has a Tales From

Beyond Science collection out next month from Image, and his Yesterday’s Tomorrows collection has "Really

& Truly" copyright him and Grant Morrison, while the Case Files 17, Judge Dredd and all

related characters and their distinctive likenesses and etc. are copyright

Rebellion A/S. For a while, that was the purportedly the lynchpin of Alan Moore

refusing to write any more of The Ballad

of Halo Jones, even above the protests of artist Ian Gibson: he wanted the

rights to the series, though he’s more recently indicated that he’s no longer

interested, much like how he (supposedly) turned down the rights to Watchmen-the-book when DC (allegedly)

slapped ‘em on the table in an effort to secure permanent spin-off rights for

unlimited sweet prequel action.

Obviously, they didn’t

need clearance at all -- just like 2000

AD can theoretically hire anybody on god’s green earth to crap out Halo

Jones IV -- though I’m unaware as to the legalities surrounding the presumably

still-active reversion language in the initial Watchmen agreement. Didn’t stop ‘em from attracting some

high-profile teams. Perhaps the situation can be dramatized via a rival bit of

work-for-hire, here from Chuck Dixon and the late, great John Hicklenton:

Call it a recessional

hymn. Partly because it’s soaring and over-dramatic; I can very much imagine

how all manner of highly skilled creative folks might participate in Before Watchmen, because they might well

have spouses and children and circumstances critically predicated on money, and

I rather think there would be money, lots of money, money in extraordinary

quantities, as much as one might read the whole situation as DC’s cutting their

silver with heavier metals. Shit, I can even imagine some of these comics being

good, despite their covers looking like the product of a creative community

that’s decided Watchmen was really all about bad-ass heroes, crazy-ass villains and rude-ass titties; who needs haunting symbolic

overtures when you’ve got the Comedian doing his best “this is my face while

I’m fucking you in the ass” routine? Yet... I mean, Brian Azzarello wrote Doctor 13; I can’t imagine one of his

series won’t carry some metaphoric charge, whether it be to criticize Alan

Moore, or DC, or just maybe track the Ditkovian hero’s progress from, say,

Rorschach being like Spider-Man in issue #1, then the early Question in issue

#2, then Mr. A in issue #3 and so on.

That’s aesthetics though. There’s

an ethical component too, if maybe not a broadly persuasive one. Business-wise,

you're always going to have a hard time convincing Americans that something is

wrong if it's not against the law, and I don't think it's ultimately a

convincing argument to very many people that you shouldn't work on a

company-owned superhero comic if one of the principals says 'don't do it' and

the other one's basically going 'have a goddamned blast,' and in doing so

you're **probably** once again delaying the return of their contractually

assured property to them -- which we might guess involved more than simply the

return of the reprint rights to Watchmen-the-book, since otherwise why would DC

offer that shit to Moore in the first place to guarantee the prequels? -- even

though it's not a black letter statutory violation of the sort that would win

you 25 in the Iso-Cube. But, you know, neither was DC not paying a stipend to

Siegel & Shuster for a long time; they were persuaded by the community into

doing that under the threat of their Superman movies becoming toxic from bad

publicity. Alan Moore, in contrast, is low-hanging fruit with fans and some

professionals alike; the bombs'll really go off if DC starts seriously fucking

with Neil Gaiman, instead of just declining to pay him commiserate with prose

publishing, which is how the Sandman 30th Anniversary project got scuttled a few

years back.

But it's a slippery

situation, this, because remember when I told you fans don’t really know who

the Punisher’s creators are? Part of that’s because they weren’t credited in

the issue from where I ripped the above image. Somebody PLEASE correct me if

I’m wrong here, but I don’t think they were credited in any of Ennis’ Punisher

comics. I don’t know about the royalty situation concerning movies or anything,

but I’m thinking they’re not making money off of miscellaneous appearances by

the character. So, much in the way that Alan Moore is arguably guilty of

Internet Sin #1: Hypocrisy in putting Voldemort in League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, one could also say that Garth

Ennis is complicit in the systemic abuse of superhero comic book creators by

simply electing to work on a corporate-owned superhero character, though

admittedly that would make Gerry Conway guilty of the same in debuting the

Punisher in The Amazing Spider-Man. And

anyway, if "creator rights," as it appears to have been redefined

this week, means refusing to trample on the rights of any creator (of scripting

or art content) to follow their legally unprohibited bliss (although the

publisher, of course, will be the legal creator in a work-for-hire context),

then really there's no way not to oppose creator rights short of keeping your

damn mouth shut or everyone being replaced by literal script and art droids.

It's all very funny to me,

because I think Garth Ennis has lived a pretty laudatory professional life. I

really do think he's conducted himself very ethically in traversing the comic

book landscape. I find him admirable. Yet he's also had to make decisions

pursuant to living a life in serialized comics, because there isn't much a

serialization apparatus anymore that both pays steadily and lets you publish

what you want, and I get the feeling from his interviews that Ennis probably

would just rather write comics he and an artist create themselves when at all

possible. But even with something like The

Boys, Ennis has readily admitted to a certain "if you can't beat 'em,

join 'em" impulse behind it; I'm enough of an Ennis tragic that I own the

dvd for Stitched, this awful

17-minute horror movie he wrote and directed, but there's a nice hour-long

bonus interview on the disc about his career, and on there he very candidly

describes looking for a way to do a monthly superhero comic his way, and I'd

expect that's because even as far back as 2005, 2006, the writing was on the

wall about how poorly any 'mainstream' comic book writer's creator-owned

miniseries work would sell without the juicy superhero hooks that Mark Millar

could bring, let alone a very longform, 60- 70- 80-chapter monthly serial. And

that started at Wildstorm, at DC, and Ennis and Darick Robertson wound up getting

the rights to that back from whatever creator participation deal was in effect

after the first few issues. Because maybe he'd behaved well with them, and done

well for them, and maybe they couldn't figure out a way to get it to work

without him, because their objections to it were almost philosophical, and it

hadn't made Watchmen money. Who's to

say? I just think Ennis conducted himself as well by him as he did by them.

And while Ennis also says

on the Stitched dvd that his writing

finally clicked into place on Hellblazer

because he'd stopped smoking pot and, more pertinently, had gotten all the

"garbage" writing out of his system, I wonder if there wasn't

something deeper to his 20th Dredd century than just providing a public school

in which to make mistakes and experiment with his personal obsessions. I wonder

if this isn't a document of a young man learning the ways of the world, of

hooking up for the first time in a professional capacity with a property he

sincerely loves and seeing, feeling, understanding the presence of its creators

and people rather than abstractions, of accepting ideas from the original

writer and developing a fruitful, happy relationship with the original artist,

and then taking that experience to the wider world of superhero abstraction.

Because while I love some

superhero comics, Douglas, the American system, the structure, is not built to

flatter creators. Rather, it's built so that the appeal of superheroes, big

superheroes, shared-universe superheroes, is in the windows each issue form

onto the alternate, virtual realities of the Marvel and DC universes. To

nurture the continued function of those universes, artists are always less

necessary than writers and editors, but in the end individual writers and

editors are less necessary than an assurance that new hands can learn to

function. Because voices are 'best' here when they sink into characters. Some

writers, like Grant Morrison -- conspicuously, I must say for the record, the

only DC pro at this time to publicly tell the Before Watchmen offer to

fuck off to hell -- nonetheless enjoy this structure, though I think for many

it still carries the odor of exploitation, of dehumanzation, of suffocated

pleas for help, a cape of souls and faces.

To read Garth Ennis

Comics, to hear his voice no matter what, does risk repetition. But to know

you’ll always see a Garth Ennis Comic, regardless of structure, is to blunt

that dread impact that crucial little bit.

“Kill Superheroes !!! Tell

your own dreams.”

- Alejandro Jodorowsky

***

Thanks again to Joe! Next week, Graeme McMillan

returns to this site for a discussion of the first collection of the most

memorable series that launched in Megazine

vol. 2's early days: Devlin Waugh:

Swimming in Blood.

This is fucking GREAT.

ReplyDeleteExhausting but excellent stuff :)

ReplyDeleteAs a sidenote, it looks to be quite obvious that at the root of writing superheroes (let's count Dredd as a superhero for the moment) is an unbreakable link to something fundamentally visceral, some unbreakable bond pertaining to base feelings, childhood trauma whatever.

As a graphic designer working for a communication agency, I'm used to dealing with ideas and the push and pull of the subjective tastebuds of clients though all visualisations are enmired in an objective framework but - though every design I churn out I really feel personal about - I would never go so far to use terms like 'exploitation' and 'dehumanization' in relation to my working relationship with the client. They hand me the tools (logo, housestyle, mission statement etc) and I visualise it, processed through my capabilities and insights. Same as with superheroes (the corporation's tools) and the writer's ideas.

If I don't like this relationship, I would go freelance just as a writer should go creator-owned if he doesn't like it. I have 'given' some great ideas to clients because of this relationship, some of which other communication agencies still build upon but that's the nature of the beast. Love it or leave it.

In short though, I think some parts come out pretty harsh in the post, particularly the relationship about writers with corporate-owned superheroes. Ennis does indeed is remarkable in the sense that he seems to follow largely his own path.

Great piece! It's always great when a blog requires more than 2 minutes to read.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, yeah, Garth's Dredd stories are not his best work (although I still prefer them over what came afterwards, as neither Millar nor Morrison, both writers I otherwise love, ever really got the character QUITE right).

Of course, IMO, Dredd wouldn't really get good again until the middle of the 90s, with serials like "The Cal Files" (very brief, but a LOT of future storylines started there) and most of alll "The Pit".

More of this, please.

I also wanna say: yeah. this was some good reading. thanks guys!!!

ReplyDeleteDamn you and your blog for getting me hooked on Dredd. I created a Dredd-related Tumblr because, amazingly, no one had snagged it yet:

ReplyDeletehttp://askjudgedeath.tumblr.com/

Great stuff, though a bit long. have you considered breaking your posts into a few parts over the week?

ReplyDeleteI agree completely about Judgement Day, it just felt like a rerun and Johnny Alpha served no point.

This is a great series, looking forward to seeing more.

JOE: "the American system, the structure, is not built to flatter creators. Rather, it's built so that the appeal of ... shared-universe superheroes, is in the windows of each issue ... To nurture the continued function of those universes, artists are always less necessary than writers and editors, but in the end individual writers and editors are less necessary than an assurance that new hands can learn to function"

ReplyDeleteLike anyone else born in the UK after WWII, I understood comics to mean DC Thomson strips like The Bash Street Kids and The Broons. Seemingly created by Thomson himself, they fuctioned as self-contained narratological mobius loops; outside of time, space and the larger world. Once you'd grown sophisticated enough to figure out their recurring tropes, you never needed or wanted to read them again and moved on to proper books. Sound familiar?

Discovering whip-smart stuff like 2000ad- with its creator credits; evolving, fallable, mortal characters; and engagement with contemporary culture and politics- convinced me that comics could continue to form part of my adult reading life. So Garth Ennis's overly-reverential stint on Judge Dredd felt like a backwards step. It seemed to signal that something I valued had forgotten what had once made it special and different.

Once their established creators had followed the money to the US, 2000ad editorial didn't appear to have any idea what to do with the *properties* they'd left behind- other than imitating the closed loop-logic of publishing predecessors like DC Thomson and DC Marvel: hiring eager, cheaper hacks to animate the corpses (literally, in Alpha's case) of other mens' original creations to dance endlessly, lifelessly, for the lukewarm pleasure of future generations of necrophiliacs.

Such bovine lassitude is made tit-twistingly frustrating by the fact that the 2000ad group's stable of young(er) writers had created some good *original* work already. Ennis's True Faith, Dicks (i) and short stories like One Bastard And His Dog; Morrison's Zenith, Bible John and The New Adventures of Hitler; Milligan's Bad Company, Rogan Josh and Skin; John Smith's Devlin Waugh, Tyranny Rex and Indigo Prime (i), were all the kind of material that would have allowed 2000ad to continue growing with its then-still sizeable readership.

(i) Originally scheduled to appear in the short-lived Revolver.

(ii) I agree with Chris Weston's view (expressed in David Bishop's Thrillpower Unlimited) that John Smith was only a good Editor away from being a great writer.

The teenagers and adults I knew who still bought comics in the early Nineties were predominantly casual readers of titles like Viz, Deadline, Hate and Eightball; titles which felt like they were connected to the real world. The mainstream US comics industry seemed, by comparison, almost entirely predicated on- and perpetuated by- the insular world of fan culture.

ReplyDeleteThe idea that anyone would buy every single title by a publisher for months on end just to follow an Event Story, seemed to belong in a different world to that of 2000ad. With Judgement Day came the realisation that 2000ad editorial had abandoned any idea of standing in opposition to somnolent bottom-feeding publishers like DC Thomson and DC Marvel- or engaging with the world and the reader outside the confines of fandom.

Ennis's ersatz run on Dredd already felt like a Pulp(y) Bad Cover Version of Wagner & Grant's Greatest Hits, but Judgement Day's appropriation of DC Marvel's marketing strategies played as a self-reflexive Soulwax Mash-up of two cheesy karaoke backing tracks.

It's telling that the prevailing figuration of Tharg around this time- in editorials, pointless in-house ads, and back cover pin-ups- is as a DJ: re-mixing and sampling other peoples' old work, oblivious to his surroundings; and maddeningly, complacently, satisfied with himself.

(i) It would have been fun to see the earnest, socially conscious cast of Third World War laying into the legions of the undead in the pages of the achingly hip *Crisis*; or Roy of the Rovers trying not to let a pitch invasion by The Sisters of Death affect his team's passing movement in the FA Cup Final.

Having gone back and read Case Files 16-19 (basically the Dredd strips that I read when I was a weekly prog reader) i was struck by how much recycling Ennis does. Babes In Arms, Innocents Abroad, The Marshal and The Chieftain are all basically the same plot. Namely, a crime happens outside the Big Meg (Mega-City 2, The Cursed Earth, Cal-Hab or Emerald Isle) and the protagonist(s) comes to the city to make their escape or settle a score. Then a bunch of people get killed before Dredd resolves the situation in a typically violent way.

ReplyDelete